The president and director of Guatemalan newspaper elPeriódico, José Rubén Zamora Marroquín, and assistant attorney Samari Carolina Gómez Díaz will spend at least three months in pre-trial detention on the basis of a single testimony and supposed evidence that Rafael Curruchiche, the head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office against Impunity (FECI), told El Faro were collected in just 72 hours between July 26 and 29.

The FECI chief told El Faro that he met key witness Ronald Giovanni García Navarijo, a former executive of the Workers’ Bank (Bantrab), in person on the first day of evidence collection. Authorities claim that in the three ensuing days they verified the former banker’s word and audio and text messages that he submitted to prepare, in the afternoon on Friday, July 29, to execute a raid of Zamora’s home and the offices of elPeriódico, where they detained eight employees for 16 hours and prevented them from contacting anyone.

At the time of the raids the Public Prosecutor’s Office froze the newspaper’s bank accounts, only to release them days later after discovering that they contained the equivalent of just $500. Despite the raid of the workplace and the frozen accounts, Curruchiche has insisted in public statements that Zamora’s detention has to do with “his activity as a businessman, and not with his journalistic work.”

On Tuesday, Aug. 9, Judge Freddy Orellana remanded Zamora in custody on charges of money laundering, blackmail, and influence peddling, and for Gómez on accusations of leaking confidential information. The audio recordings, text messages, and cash presented in court in hearings that Monday and Tuesday were all provided by García Navarijo. Defense attorneys Christian Ulate and Armando Mendoza argue that the evidence is based solely on the testimony of a man accused since 2016 of money laundering and embezzlement. They also assert that the Public Prosecutor’s Office tampered with evidence.

García Navarijo filed a criminal complaint against Zamora on July 26. During the pre-trial hearings prosecutors asserted that the plaintiff told the FECI that Zamora blackmailed him into laundering 300,000 quetzales ($40,000) in cash by threatening to publish evidence of the former banker’s criminal ties.

He claimed that Zamora “probably” obtained the money by extorting others and that the journalist obtained the information against him from the former FECI chief Juan Francisco Sandoval, exiled in the United States since July 2021 after Attorney General Consuelo Porras illegally fired him. The same judge now trying José Rubén Zamora, Freddy Orellana, issued one of two arrest warrants for Sandoval.

Prosecutors assert that the parties had agreed that García Navarijo would deposit the funds in the account of one of his businesses and then write a check in the same amount to Aldea Global, the newspaper’s parent company.

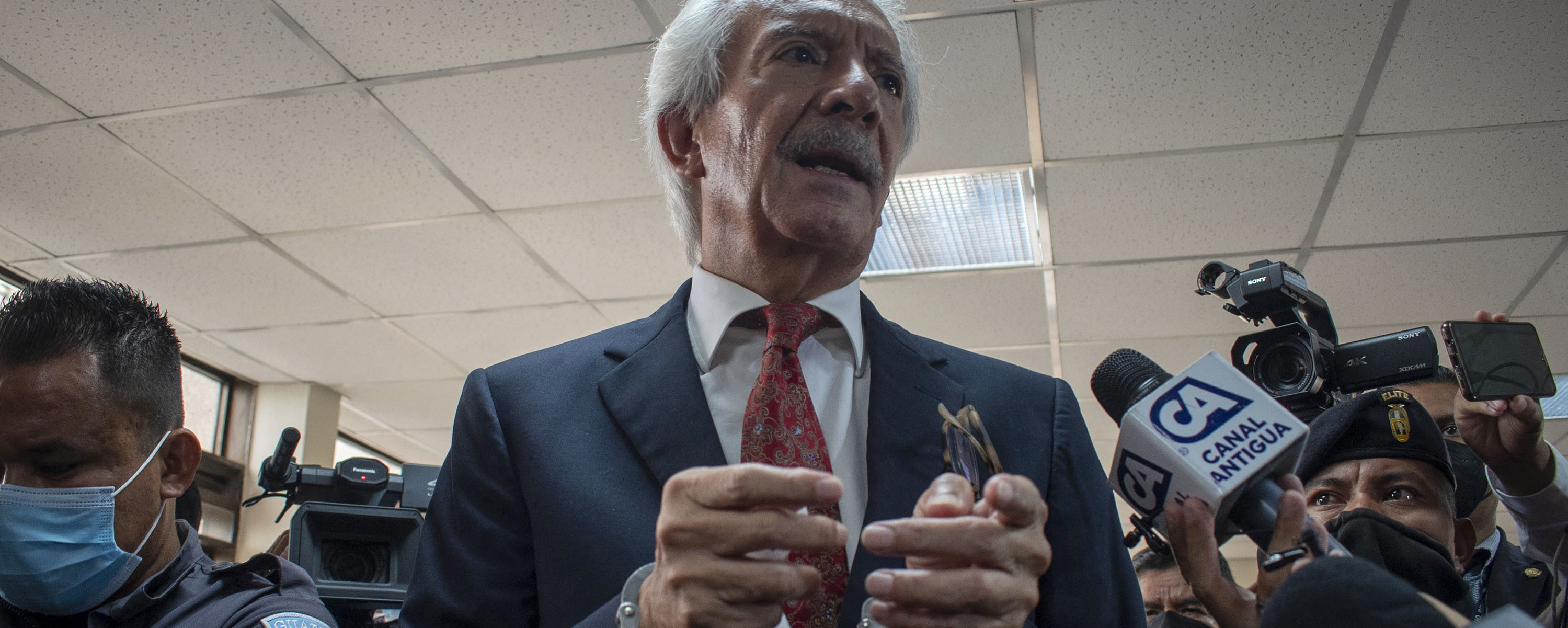

In his first hearing on Aug. 8, Zamora acknowledged to the judge that he gave García Navarijo the amount of money reported in his indictment. In a recess he told the press that he received the cash from “two businessmen who wanted to support elPeriódico.” Zamora’s attorney, Christian Ulate, told El Faro that the purpose of the triangulation was to protect the identity of the donors, per their wishes, from any kind of retaliation. Zamora says he hopes the two businessmen who gave him the money will come forward to dispel the allegations.

He has also told the press that he has known García Navarijo for almost two decades. “We never had any issues,” he claims.

The defense argues that the money that prosecutors presented in court could not be reliably attributed to Zamora because, contrary to when they allege he gave the money to García Navarijo, the stacks of cash were displayed in court without currency bands. The detail could be key to his defense, given that the bands, placed on bills by banks at the time of withdrawal of large sums of cash, would test prosecutors’ assertion that the money was obtained illicitly.

“My client has always held that the money had bands from Banco Industrial because it had been withdrawn from there,” said Ulate. “You don’t launder money already in the banking system,” he continued. On July 31 and Aug. 1, government-aligned social media accounts published a photograph of the alleged money with bands — information that, if real, would have been illegally leaked from the case file on social media, along with some of the audio files presented by prosecutors in court.

The defense says that joint plaintiff Raúl Falla —an attorney from the Foundation Against Terrorism (FCT) who is representing García Navarijo— saw these bands.

When prosecutor Cynthia Monterrosa displayed the supposed bills in court on Aug. 8, she removed bandless stacks of bills from envelopes with the seal of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, without using gloves. That could complicate the defense attorney’s request that the bills be examined with ultraviolet light to determine whether they were the same that Zamora received from the businessmen.

Sources in the banking system told El Faro that another possible method of verifying the money’s origin would be the record kept by Banco Industrial with the serial numbers of bills removed in high quantities.

Two Former Presidents

At the time García Navarijo filed the criminal complaint with the FECI he had yet to receive the money from Zamora. The journalist’s driver dropped off the money on July 28, two days after the filing. The driver arrived at 3:30 p.m., the defense asserted, and the FECI carried out its inspection two hours later. By then, the bills’ bands had been removed, per pictures submitted as state evidence.

García Navarijo and other Bantrab executives were investigated by the anti-corruption commission CICIG in 2016 —as elPeriódico reported— for diverting $3.4 million in bank funds to companies owned by its executives, as well as to the 2011 presidential campaign of Otto Pérez Molina. Authorities issued an arrest warrant for him in 2016 but he evaded capture until 2018. A year later, after the expulsion of the CICIG, he was released to house arrest and began to collaborate as a state’s witness.

In remarks to the press on Aug. 3, Zamora said that García Navarijo was worried that the state would change the terms of his cooperation agreement under which he confessed to multiple crimes. The president of elPeriódico says that García Navarijo told prosecutors that he provided money laundering services to Salvadoran ex-president Mauricio Funes (2009 - 2014) and Guatemalan ex-head of state Jimmy Morales (2015 - 2019).

Former FECI chief Juan Francisco Sandoval confirmed to El Faro on Aug. 13 that García Navarijo confessed to laundering money for former public officials. He did not name them, but said that the Attorney General’s Office should have more information.

“You’ll be surprised at the evidence we have,” Curruchiche told El Faro three days before the first pre-trial hearing. Prosecutors will now have to prove their charges on the basis of what they presented in court to argue for a trial. Curruchiche says prosecutors have corroborated all evidence, including emails, phone calls, and “elements of investigation obtained according to the law.”

He also says that García Navarijo is not a state collaborator nor a protected witness. “He asked for a cooperation agreement, and I conferred with the prosecutor [Cynthia Monterroso], to see whether the information he provided was useful and complied with the Organized Delinquency Law, and it didn’t meet the requirements,” said Curruchiche, but he did not rule out the possibility of a future agreement.

The defense holds the opposite: that García Navarijo is testifying in exchange for his exoneration and that authorities made arrests first to later see what they could prove.

The lead prosecutor working the case, Cynthia Monterroso, has a troubled track record. In 2019, now-exiled judge Erika Aifán called on the attorney general to investigate her for removing and planting courtroom evidence. It was no use; in 2021 Porras even halted an arrest warrant against Monterroso issued by Sandoval. According to digital news site Soy502, Judge Freddy Orellana was the only judge to agree to move forward with the case presented by the FECI and the far-right advocacy organization FCT against Zamora and Gómez. The outlet published a private picture from 2021 of the judge at a shooting range with a member of the foundation, implying a personal relationship.

“This is a political hit job fabricated by the president [Alejandro Giammattei], the attorney general, and others,” Zamora has said about the accusations against him. In an Aug. 4 editorial, The Washington Post called the charges against Zamora “spurious.” The Inter-American Press association called the operation against Zamora and elPeriódico “disproportionate” and argued that it “suggests that the Guatemalan government is seeking to silence this media outlet known for its denunciations of corruption.”

For months Zamora has publicly stated that the government was looking to “mount a case to lock me up.”

On the day of the raids, and at the order of the FECI, the police climbed down from Zamora’s roof onto an interior patio instead of ringing the doorbell, despite having obtained a search warrant from Judge Orellana to enter through the front door. Gómez was detained the same day in the FECI offices. Both now await trial in the military prison Mariscal Zavala in Guatemala City, a facility incarcerating former officials who Zamora has written about and who Gómez has investigated in recent years.

García Navarijo cited unspecified “threats” against him in his decision to not attend the hearings. Raúl Falla, the attorney representing him, and FECI chief Rafael Curruchiche have been sanctioned by the U.S. State Department on accusations of obstructing justice. The FCT, Falla’s organization, is one of the lead architects behind a wave of criminal complaints against independent justice system operators. For years the organization has publicly defended members of the Armed Forces accused of human rights violations and condemned the charges of genocide against ex-president Efraín Ríos Montt.

The Recordings

None of the audio recordings that the FECI played in the pre-trial hearings show Zamora asking García Navarijo to launder money, threatening the former banker with publishing damaging information unless he deposited the money, or stating that he had obtained the funds illicitly. Prosecutors have also yet to present evidence that Zamora obtained the money collected as evidence through blackmail and have thus far relied solely on García Navarijo’s testimony.

A recording of prosecutor Samari Gómez similarly did not show any evidence supporting the accusation against her of leaking confidential case information.

In one recorded call on Aug. 9, 2021, just six days after Curruchiche was named as head of the FECI in Sandoval’s place, Zamora had called a meeting at his home with his attorneys Mario Castañeda and Romeo Montoya to discuss how to register in the paper’s accounting records 200 thousand quetzales ($26 thousand) received from ARCA, a firm created by the executives of Bantrab supposedly for marketing purposes. In a 2018 statement to the FECI, Zamora said the money was a loan from Eduardo José Liú Yon, a Bantrab executive, one of the board members alongside García Navarijo to be indicted for the embezzlement of the $3.4 million in bank funds.

After the hearing on Aug. 3, Zamora asserted that he sometimes received advance payments from banks and advertisers and decided what to do with the money as needs arose. In the meeting at his home in August 2021, due to the Bantrab case and the change of leadership at the FECI, those present agreed that he needed to put on paper what he ultimately did with the money from the check. One possibility was to record it as publicity sales, given that the bank was one of elPeriódico’s advertisers.

Prosecutor Monterroso claimed that the recording showed Zamora and his attorneys conspiring to hide the origin of the money, but in reality it revealed García Navarijo explaining how they could justify the check, with phrases like “I have the seals,” meaning that he can notarize documents. “Here the active person was García Navarijo,” argued defense attorney Ulate, continuing: “He [García Navarijo] proposes: ‘I think we should do it like this.’ He says [to Zamora]: ‘You’re named in a CICIG report.’ He gives the information to José Rubén Zamora.” Ulate called the plaintiff “the provoking agent” in the call.

In another call played in court between García Navarijo and assistant prosecutor Samari Gómez, and contrary to the plaintiff’s claim that they showed evidence of influence trafficking, they had a standard conversation about the terms of a cooperation agreement. Nor did they even mention José Rubén Zamora or Juan Francisco Sandoval. The recording does reveal García Navarijo stating that he wanted to postpone his deal with the FECI: “I’ll cooperate, but not for the next few months. I need to gauge the winds.”

Zamora’s legal team questioned the legality of the recordings, claiming that García Navarijo illegally obtained them without the consent of involved parties. They also argued that under normal processes the Public Prosecutor’s Office would have responded to the filing by initiating an investigation and filed wiretapping requests for the phones of the accuser and the accused, rather than leaving evidence collection to the plaintiff. García Navarijo recorded one of the conversations after filing the report, the defense noted, when authorities would have had the authority and obligation to obtain a wiretap.

Possible Ulterior Motive

Zamora says that García Navarijo visited his home in the last week of June to complain that the Public Prosecutor’s Office had not unfrozen 33 million quetzales ($4.4 million) from an account in his name. Present at the time was Manfredo Marroquín, the director of transparency advocacy NGO Acción Ciudadana. “[García Navarijo]” literally told me, and Manfredo Marroquín witnessed it, that Mr. Curruchiche asked for 15 percent [of the money] and for him to burn people bothersome to the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the sitting administration,” claimed Zamora, adding that he told the former banker not to give in.

Marroquín confirmed to El Faro that he was present for the encounter and heard the allegation against Curruchiche. He says García Navarijo felt that “they wanted to screw him” for statements that he made to the FECI under Juan Francisco Sandoval’s tenure, like the admission that he laundered money for Mauricio Funes and Jimmy Morales. Marroquín says that the now-plaintiff told them that “I won’t play along” and that he didn’t want to pay.

On Aug. 5, Curruchiche told El Faro that he could not have asked for a cut of the money because it was in accounts “embargoed since 2016 and facing civil asset forfeiture.” He added that the accounts belong to Bantrab and are in the name of four other people.

“Four weeks ago [García Navarijo] asked for the embargo to be lifted,” said Curruchiche. “The FECI was opposed because it’s money from salaries and allowances. It’s an illegal way to take funds from the Workers’ Bank and the Prosecutor’s Office for Civil Asset Forfeiture is handling the case.” On Aug. 5 digital outlet Soy502 wrote that, according to Asset Forfeiture Judge Marco Villeda, the specialized court has no case tied to García Navarijo.

Per Curruchiche, the FECI rejected the request to free the funds in mid-July, though outlet Plaza Pública reported that a judge unfroze the account on the 18th of that month. Prosecutors assert that García Navarijo and Zamora spoke over the phone the next day of the 300 thousand quetzales in cash to be deposited in one of García Navarijo’s accounts and then for a check to be written to elPeriódico for the same amount.

Ulate argued this could not have been carried out because the frozen accounts would have prevented García Navarijo from depositing and cutting a check. He also mentioned a text messaging conversation between his client and the plaintiff: “José Rubén Zamora tells him that he has financial problems, that ‘I’m finding money.’ He doesn’t say, ‘Launder this money for me.’ Then Ronaldo García Navarijo tells [the FECI] that ‘I think the money comes from blackmail.’”

García Navarijo had a hearing for the Bantrab case on July 25 but did not appear, citing sickness with Covid-19. The next day, as the accounts —per Curruchiche— were still frozen, he arrived at the FECI at 10 p.m. and filed the criminal complaint against Zamora.